ANALYSIS

There's no case for a corporate tax cut when one in five of Australia's

top companies don't pay it

By chief economics correspondent Emma Alberici

Updated Wed Feb 14, 2018 at 11:53am

PHOTO: Qantas is about to clock its

10th year tax free, while its CEO Alan Joyce takes home a $24.6 million

salary. (AAP: Joel Carrett)

PHOTO: Qantas is about to clock its

10th year tax free, while its CEO Alan Joyce takes home a $24.6 million

salary. (AAP: Joel Carrett)

There is no compelling evidence that giving the country's biggest

companies a tax cut sees that money passed on to workers in the form of higher

wages.

Treasury modelling relies on theories that belie the reality that's

playing out around the world.

Since the peak of the commodities boom in 2011-12, profit margins have

risen to levels not seen since the early 2000s but wages growth has been slower

than at any time since the 1960s.

INFOGRAPHIC: Company profits are at their

highest point since 2011 but wages have stagnated.(The

Conversation (ABS business indicator and wage price index))

INFOGRAPHIC: Company profits are at their

highest point since 2011 but wages have stagnated.(The

Conversation (ABS business indicator and wage price index))

It's also disingenuous to talk about a 30 per cent rate when so few

companies pay anything like that thanks to tax legislation that allows them to

avoid paying corporate tax. Exclusive analysis released by ABC today reveals one in five of

Australia's top companies has paid zero tax for the past three years.

And while the Treasurer and Finance Minister warn that Australia's

relatively high headline corporate tax rate means Australia remains

uncompetitive and companies will choose to invest in lower taxing countries,

the facts don't bear that out. Business investment in Australia has been

at historically

high levels over much of the past decade despite our comparatively

high headline corporate tax rate.

PHOTO: US President Donald Trump

signed the tax bill in December, cutting corporate tax rate to 21 per cent from

January. (AP: Evan Vucci)

PHOTO: US President Donald Trump

signed the tax bill in December, cutting corporate tax rate to 21 per cent from

January. (AP: Evan Vucci)

There's more to

investment than corporate tax rates

Before Donald Trump cut the US corporate tax rate earlier this year, it

was 5 to 9

percentage pointshigher than Australia's. That hasn't deterred

Australian companies from seeking opportunities in America instead of Ireland,

where the corporate tax rate is less than half ours (12.5 per cent), or

Singapore (17 per cent).

In truth, businesses make decisions about where in the world to park

their money based on myriad reasons, possibly least of which is the headline

corporate tax rate.

Will I be closer to my main customers? Where is the best talent located?

What are the labour costs? How onerous are the regulatory hurdles to

investment? Is the culture and language easy to navigate? Is the country

politically stable and is there respect for the rule of law?

When Incitec Pivot chose to build a

$1 billion factory in Louisiana rather than Australia, it did

so due to America's strong productivity levels and its speedy approvals

processes. Tax was insignificant on the pros and cons list.

Tax rates don't

matter if you're not paying tax

High-profile chief executives like Qantas chief Alan Joyce are adamant

that investment decisions rest largely on the rate of a country's corporate

tax. But it's hard to see how a lower tax rate is an incentive for investment

when one in five of our biggest companies haven't paid any corporate tax at all

in at least three years.

Qantas is about to clock its 10th year tax free. Qantas won't pay tax

again until its profits exceed the tax losses recorded since 2010. Only when

all the accumulated losses are offset will a lower tax rate mean a higher cash

flow. Besides, regardless of where the corporate tax rate sits, the airline has

already indicated an intention to invest $3 billion

across 2018 and 2019.

The overwhelming benefit of higher profits flows to shareholders. A zero

corporate tax bill at Qantas has certainly seen one significant wage rise at

the company — the chief executive's. The benefit to workers has been less

pronounced.

According to the Australian Services Union, representing just under half

of all Qantas workers, the average pay rises for staff since the airline has

returned to profitability have barely kept pace with inflation.

Alan Joyce, on the other hand, has seen his total salary

close to double from $12.9 million in 2016 to $24.6 million

last year thanks to a huge jump in the value of shares provided as part of a

bonus scheme.

Linda White, Assistant National Secretary of the Australian Services

Union told the ABC she is far from convinced about the value for workers of a

corporate tax cut:

"While Qantas

workers have seen pay rises of less than 3 per cent on average over the past

decade, we've seen the CEO's salary balloon to almost $100,000 a day — much

more than most workers earn in a year. It doesn't trickle down — it trickles

up, and the rules need to change to give workers a better deal in this

country."

The apples and

apples comparison

When drawing comparisons with experiences in other countries, Canada

provides a good like for like profile.

Australia and Canada share a similar history and are both resource rich

economies. Our financial and political systems are also on par.

Canada cut its corporate tax rate from 42.4 per cent in 2000 to about 26

per cent in 2011, where it has remained. In 2000, Australia cut its

corporate tax rate from 34 per cent to its present 30 per cent.

Business investment rose in both countries during the mining boom but it

rose more in Australia, despite a corporate tax rate that's four percentage

points higher than Canada's.

Economist Saul Eslake says:

"It can be

argued that the mining investment boom was bigger in Australia than Canada but

now that it's over in both countries, it's worth noting that business

investment as a share of GDP was 2.4 per cent higher in Australia in 2016 than

in 2000, as against only 1.5 per cent higher in Canada, despite Canada's

massive cut in company tax."

It is also worth noting that wages have risen by about 20 per cent more

(in nominal terms) in Australia than in Canada since 2000, despite Canadian

companies having had a much bigger corporate tax cut.

Media player: "Space" to

play, "M" to mute, "left" and "right" to seek.

Do workers really

win?

The White House

claims the recently legislated cut in the US corporate tax rate

will translate to higher wages for the average worker of between $4,000 and

$9,000 a year, but there is no credible evidence to support that boast.

In fact, the opposite has been true in practice when you compare

business activity in Britain and America. Between 2006 and 2013, while British

businesses were paying increasingly less in tax (from 30 per cent to 19 per

cent), wages went down not up. UK wages have started to grow over the past four

years but at a much slower rate than in the United States where corporate tax

rates had remained high.

INFOGRAPHIC: Comparing corporate tax rates

and median wage growth for workers in the US and UK.(Supplied:

OECD, UK Office of National Statistics, Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, US

Federal Reserve )

INFOGRAPHIC: Comparing corporate tax rates

and median wage growth for workers in the US and UK.(Supplied:

OECD, UK Office of National Statistics, Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, US

Federal Reserve )

Some commentators

have seized on a study from Germany to support their theories

about corporate tax cuts trickling down to workers. Saul Eslake makes the point

that the German economy is not all that similar to Australia's:

"Among other

things, workers' representatives sit on the 'supervisory boards' of large

German companies so there is probably a different debate within German

boardrooms as to how the benefits of any cut in the corporate tax rate in

Germany might be shared among employees and other stakeholders."

In his speech last week, the Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe

reiterated the need for Australia to pursue an internationally competitive tax

system but he did not specify which, if any parts of the Tax Act, might need

amendment. He kept his comments on the topic vague:

"The issue of how the tax system affects the competitiveness of

Australia as a destination for investment is one of ongoing political

debate."

The headline 30 per

cent rate is misleading

Adding to this debate is the issue of average and effective tax rates.

Effective tax rates are said to drive investment decisions and take account of

what companies actually pay once deductions, depreciation and other tax

minimisation strategies are considered.

According to a report published

last year by the US Congressional Budget Office, Australia's

effective tax rate, at 10.4 per cent, is among the lowest in the world.

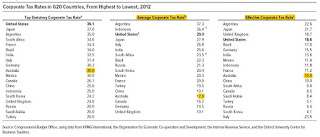

INFOGRAPHIC: How Australia's corporate tax

rate compares to others around the world. (Supplied: US

Congressional Budget Office)

INFOGRAPHIC: How Australia's corporate tax

rate compares to others around the world. (Supplied: US

Congressional Budget Office)

The average rate paid by American companies in Australia is just 17 per

cent.

The Treasurer's office takes issues with these figures, claiming they

are out of date because they are based on data from 2012. The Government

prefers a study by

Oxford University that puts Australia's effective average tax

rate at 26.6per cent and at the higher end of the scale.

Several analysts consulted by the ABC disagree. Managing director of

Plato Investment Management, Don Hamson says:

"Whilst the

data used in the 2017 CBO report is from 2012, it is the best analysis

available and I don't believe the Australian company tax landscape has changed

significantly since 2012."

Dr Hamson has worked in banking and finance in Australia, as a

university professor in Australia and the United States and has served on the

ASX Corporate Governance Council.

Regardless of which effective tax rate you prefer, both the Oxford and

the CBO data demonstrate the folly of focusing exclusively on the headline

corporate tax rate of 30 per cent.

Do tax cuts boost

investment?

Chris Richardson from Deloitte Access Economics told the ABC's Q&A

that there was a "consensus" from the experts about the macroeconomic

benefits of a corporate tax cut.

He said the cut represented $20 billion a year in growth for the

Australian economy with two out of every three dollars showing up as higher

wages. Those figures (and experts) came from

Treasury who provided modelling on behalf of the Government.

Will Australia really be uncompetitive with these countries if the Government's tax cut proposal is not passed by Parliament?

The numbers are based on the widely, but not universally, accepted

theory that cutting the company tax rate will raise investment, which should in

turn boost productivity and lift wages.

Apart from the obvious point that all else is not equal in practice, not

all investment boosts labour productivity.

According to other

Treasury-commissioned modelling, if the rate is lowered from 30 per

cent to 25 per cent then gross domestic product will double by September 2038

as opposed to December 2038 without the cut. Both models predict that in 20

years' time the unemployment rate will be 5 per cent regardless of whether we

spend $65 billion on company tax cuts or not.

In truth, it is hard to find real-world evidence to support these

economic theories, so the Government might be wise to heed the words of Plato:

"A good decision is based on knowledge and not on numbers."

Dividend imputation

often overlooked

The other issue often overlooked is the impact of Australia's dividend

imputation system. Australia and New Zealand are the only two countries in the

OECD that grant companies the right to attach tax credits to dividends paid out

to investors.

In most countries, companies pay tax and then shareholders pay tax on

their dividends. Australia taxes just once. Cutting the company tax rate

therefore doesn't result in a higher after-tax return on investment to

Australian shareholders in Australian businesses so Treasury's theoretical

model doesn't hold.

Experts including economist Saul Eslake estimate that Australia's 30 per

cent corporate rate with dividend imputation raises about as much tax for the

government as a 20 per cent rate without dividend imputation.

The principal beneficiaries of a cut in Australia's corporate tax rate

are overwhelmingly foreign companies and foreign shareholders in Australian

companies. There is no guarantee at all that cutting the tax they pay in

Australia will lead them to increase the level of business investment in

Australia.

PHOTO: The last time tax cuts were on

the table was when treasurer Peter Costello was in the chair. (Alan

Porritt: AAP)

PHOTO: The last time tax cuts were on

the table was when treasurer Peter Costello was in the chair. (Alan

Porritt: AAP)

Can Australia

afford to spend $65 billion?

The last time a government splashed around cash in the form of tax cuts

the treasurer was Peter Costello, who had no debt and no deficit to contend

with, thanks to oversized profits and attendant corporate tax flowing from the

mining boom.

In 2018's Australia, it's hard to imagine how a government could ever

again manage to give away the equivalent of Mr Costello's $170 billion worth of

tax cuts while still protecting the surplus.

It's been 10 years since the Australian budget was last in surplus. With

a debt of more than $600 billion, many are questioning the merits of

prioritising a $65 billion giveaway to big business in the form of a tax cut.

Back in November 2016, the president of the Business Council of

Australia, Grant King was warning the Government not to put the country's AAA

credit rating at risk by ignoring budget repair. He told ABC's AM

program:

"We are seeing

indications that the deficit is deteriorating so it is going to be a

challenge."

Yet today the BCA and its high-profile members like Mr Joyce are

insisting on a company tax cut that would blow a massive hole in the

Government's revenues and push the budget and national debt further into the

red.

First posted Wed Feb 14, 2018 at 5:42am

Source -

Friday, February 16, 2018

0 comments:

Post a Comment